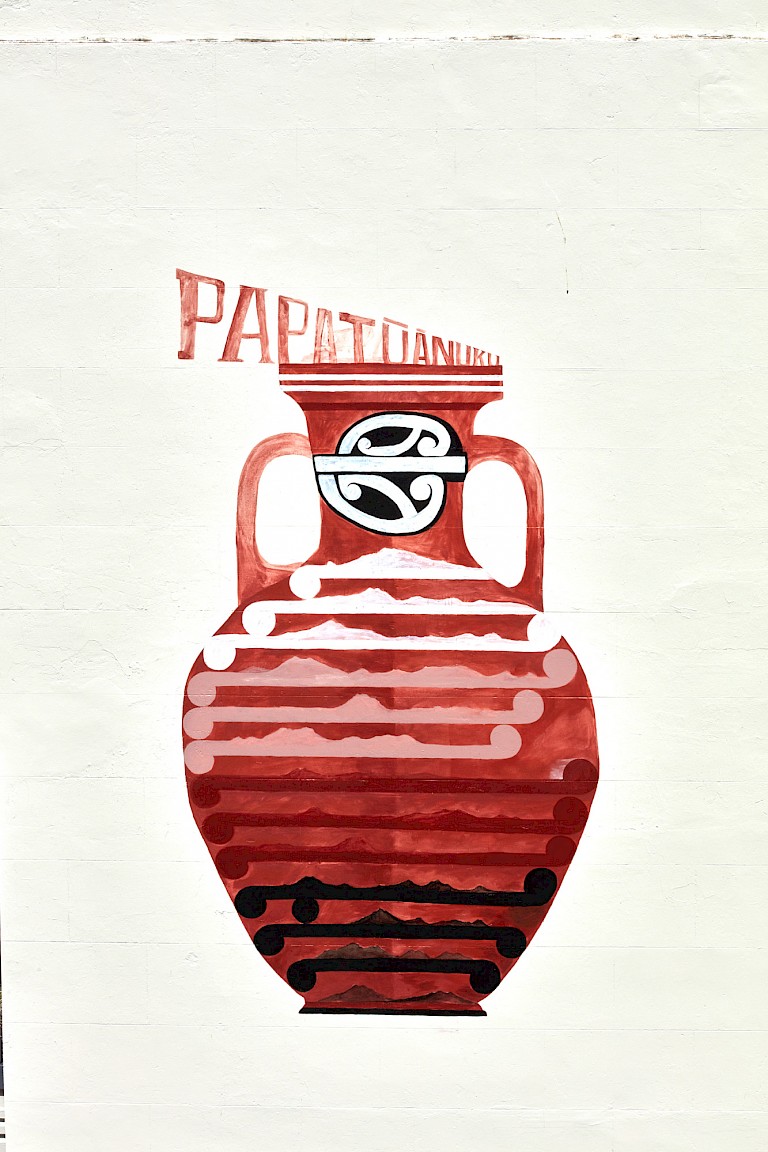

The basis of the Maunga is a series of 25 works on paper created by Shane Cotton in response to Britomart’s commission. He and artist Ross Liew collaborated on the translation of those works into the five-storey-high artwork that now occupies the corner of Customs Street East and Commerce Street.

The space is part of Auckland’s transportation hub - the central station for the cities metro network, and so the work is meant to reflect the diversity of the people that move in and out of the city, and the places they have come from, the stories they bring with them. Auckland is a volcanic plateau, defined by the volcanic cones that break and disrupt the surface, and historically many of them were pā sites, or Māori fortified villages, usually with terraced approaches, fenced structures, and entry gates. The motif of these pā, mountains, and pots appeared frequently in Cotton’s paintings throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, along with architectural structures, stars, ships, flags, birds, teapots, and mono mokai (disembodied tattooed heads), indicative of the frequently abrupt and violent interplay and exchange between colonized and colonizers, the native and the landed.

Here, pots operate as a more benign object of currency and exchange - pots were carried by colonial settlers across vast distances, used to carry personal belongings as well as plant specimens for food as well as propagation. Once they arrived, the plants and the pots were often traded with local iwi (tribes) and became a decorative feature in wharenui (meeting houses). The pot, with its little microsystem of soil and plant matter, is symbolic of home, thus here, each pot then represents a place from around New Zealand, as if carried there by someone arriving on the train network.

Of course, it also relates to cultural exchange and the ways and means that Māori adapted to the introduction of European belongings, customs, technology, and imagery, both as a matter of cultural selection and a means of survival. Many examples of technological adaption are evident from the early cultural period - European blanket fires being woven into cloaks (korowai), musket grips carved with upoko (faces) to represent alertness, and of course, paint and figurative painting. Cotton’s work frequently refers to the adoption of figurative painting by adherents of the Ringatū faith, and Te Kooti - an Anglican lay preacher, exiled spy, and visionary spiritual leader who, upon his return from exile, led a band of acolytes in raids against colonial settlers, led a military campaign against the Crown. Cotton’s imagery relates both to this history and to the adoption by Ringatū of European religious concepts, icongraphy, and the painting tradition.

As a symbol, the pot is also redolent with Māori’s connections to the land - Māori are self-referentially, tangata whenua, people of the land - a title that implies guardianship, kaitiakitanga, of the land, the environment, and the people within.

It is impossible to view Cotton’s work in isolation, rather it is the latest in a series of works by Māori artists in the city that follow the paths of the old streams and rivers, now underground waterways of Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland). So it is fitting that of the two commissions that Cotton produced in conjunction with Toi Tū Toi Ora, the work in the Auckland Art Gallery is a skiff, not unlike one would see launched from a visiting British ship, and the painting on the outside wall of Excelsior House is a series of vessels. The selection of the building and its location approximate to the city’s waterfront, across the street from the ferry terminal and the old Customhouse reinforce these watery associations.

The references too, to the trade and exchange that occurred between Māori and pākehā (Europeans) in the earliest colonial period are reflected in the building itself - Excelsior House was built as a bonded warehouse for the goods that came off the ships.

Cotton’s work assimilates these various strands - voyages and homecomings, departures and arrivals, customary and nascent, introduced and indigenous - and mixes them up with his personal visual vernacular, and creates a work that functions to acknowledge the history of the site and subtly nudge toward issues of nation building in a colonial context.

Cotton’s Maunga relates to a series of mountains and places around Aotearoa New Zealand that are in some way personal to him, either places that he has visited or locations with some imaginary association. The locations themselves aren’t necessarily meaningful beyond a fleeting connection, or as reference to the spark of a memory, and, located as they are on the wall of a transit station, they conjure the kinds of fleeting sense of recognition that travelers often have, association with out fixity.

An element of this work that I find interesting, although I admit that I haven’t decided the how of it, is the fact that this is an extraordinary departure from Cotton’s practice. Cotton is a very painterly painter. Of the contemporary Māori artists to have established themselves in the past three decades, he is perhaps the most traditional in terms of his use of the medium, and rarely does he stray from a very formal figurative style steeped in tradition and technique, so it is very unusual to see him working in a way that engages with a manufactured process, almost through instruction. His painterly style has survived the translation intact, but quite what it does in this new format, I have yet to settle on. Nevertheless, it is an interesting development in Cotton’s style and process and it will be intriguing to watch and see if it has any long term implications.