While recognising a potential risk of rekindling forms of conflict, the artist of Bosnian Girl sought to promote a rethinking of the relationship between Bosnia and the Netherlands. The understood the need to move beyond a sense of guilt, seeking to ensure a different relationship in the future, and to avoid a more polarised world. For this purpose, journalists were asked to interview the young people, especially about how they want to commemorate this moment in the future, and why and how they want to share knowledge with other Bosnians and Dutch people.

The installation consisted of 25 large photographs, two by three metres, accompanied by the stories of the people portrayed, as well as their connections to the event.

Each year new remains of victims are found, so each year new names are spoken aloud during a ritual narration. During the commemoration, people walk in a circle while these names are spoken. The photographs in the square at The Hague are also arranged in a circle to emphasise this ritual, creating a more intimate space around the ceremony. Among the participants were the older generation who had directly experienced the war, and who proposed many ideas for future commemorations. A representative of the Ministry of Defence attended the event for the first time, giving a public speech during the opening.

The commemoration was a critical moment. In attendance were the 25 young people, portrayed in the photos, who lost their parents and other family members. Also present were young people of Serbian or Croatian backgrounds. These two groups never met. Thus, the subject of the commemoration is never discussed, rendering the collective trauma a more deeply rooted taboo.

The common space created by Srebrenica is Dutch History moves far beyond rhetoric of a generic relational approach, and beyond the evocation of democracy as an abstract, absolute value. The temporary monument brought mothers and fathers to speak with sons and daughters. People were not divided into the categories of Bosnians, Serbs and Croats. Surprisingly, soldiers from the Dutch battalion were also present. For the first time, they spoke to the survivors, and their sons and daughters.

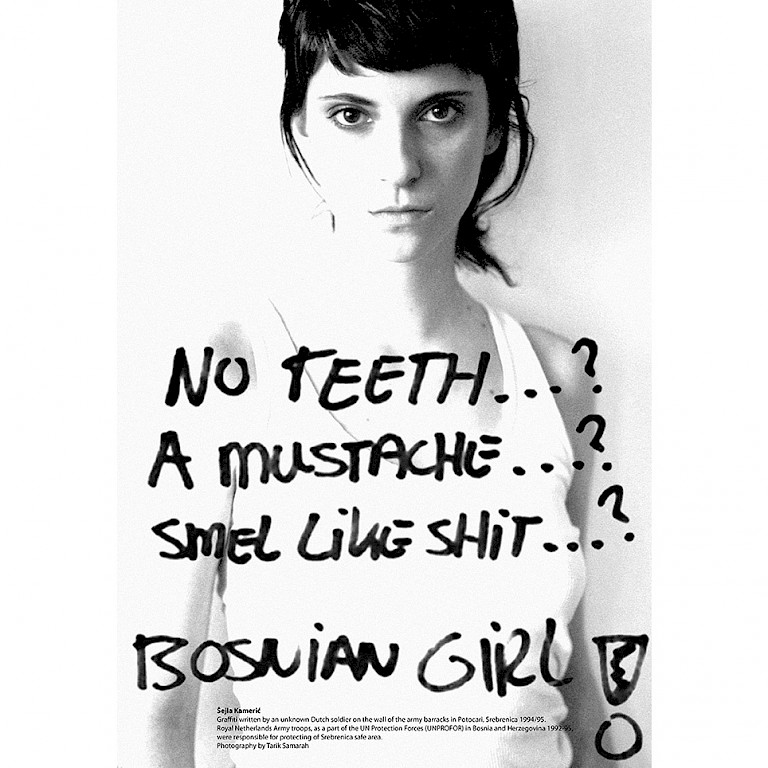

Another critical point raised by the artists concerned the dominant media narrative of the commemoration: the women, the mothers or wives of the murdered men, were portrayed in their most intense pain. In fact, we are talking about very strong women who have been fighting for justice for years, who have even been the victims of a media victimisation process. Consequently, one of the aims of the project is to show a different and more realistic image of survivors and their family members from the rhetoric and media narratives. An important and well-known precedent was set by the artist and model Šejla Kamerić, who, in 2003, realised Bosnian Girl, a public project consisting of postcards, posters and billboards.

The most famous intervention from Bosnia Girl is a black-and-white fashion-style photograph of the artist by Tarik Samarah, which shows denigrating phrases about Bosnian women superimposed on the image of a strong young woman, who was Šejla Kamerić herself, looking directly into the eyes of the visitor. Samara was questioning the viewer's own reaction to these phrases which read: "No teeth...? A moustache...? Smell like shit... ? Bosnian girls!"

The phrase was taken from graffiti written by an unknown Dutch soldier in 1994-1995, a member of the Royal Netherlands Army who, as part of the UN Protection Force (UNPROFOR) in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992-95. This unit was responsible for protecting the safe area and the people of Srebrenica. Samarah's work became a symbol not of genocide, but of the strength, pride and power of Bosnian women, who were able to reverse the narrative and create their own place in the cultural, political and social world out of the victimisation depicted. This image, which was widely shown at the time, even on billboards and by the famous women commemorating the genocide, inspired the artists who contacted her and won her support for the project. The collective also decided to take the name of the image, Bosnian Girls.

At the time of the war, Šejla Kamerić was a teenager working as a model in Sarajevo. For 4-5 years she and her family lived in an open-air prison surrounded by Serbian soldiers.

In this sense, the artist, who also wrote a manifesto, which was actually a real petition signed by 19,000 people, didn't simply state or announce a commitment, but proposed a path articulated in three steps corresponding to three goals to be achieved:

1. "Dutch history and social education pays more attention to the Srebrenica genocide and is taught in an inclusive way."

2. "The creation of a permanent national monument in The Hague where all citizens can commemorate."

3. "Structural government funding for the annual commemoration of the Srebrenica genocide in the Netherlands."

The temporary monument was placed next to the Parliament for three weeks, which was an important factor in getting the politicians who cross the square every day to deal with this event in a different way, by getting closer to the people's story. Finally, between 2020 and 2021, the temporary monument will travel to different cities in the Netherlands, including Amsterdam, to reach a wider audience in the country.

Despite the sensitivity of the subject and the difficulty of the dialogue that still exists, since it is a historicised but not so distant event, the artists have decided to take the risk of exposing themselves to criticism, even from Bosnians, by trying to activate a different type of narrative on the one hand, and by proposing a vision of the future that overlaps with that of the past on the other. This doesn't mean substituting or partially erasing it, on the contrary, it means delegating the commemoration and the building of future bridges to the next generation, which, as the artists say, is ready to step up and do things in its own way. In this case, delegation doesn't mean the "transmission" of an inherited idea, but rather the passing of the baton.

This intergenerational handover was achieved through a circular ritual in which the youngest took on the responsibility of finding new ways between the two identities, that is, the two contexts, and new possibilities, not as a generic form of acceptance and coexistence, but as a deeper, even paradoxical, constructive form of interaction.

As the artists explain, "... in a situation of genocide, everyone has their own experience and perspective, and everyone comes from a different position. In order to have a real conversation, you have to see where someone else is coming from, because it affects your future decisions and your future actions". That's why they emphasised the importance of physicality, of establishing sensory relationships, which could only be possible thanks to the creation of a conceptually safe place for all participants, transforming an institutional public space into a shared psycho-physical terrain for what we could call "agonistic interaction." (Bosnian Girl)

In fact, as the artists say, this made it possible to activate, embrace or even reject "the shift from induced separation to the struggle for connection", knowing full well that another participatory approach "would require the availability of consensus without exclusion, which is precisely what the agonistic approach reveals to be impossible" (Mouffe, 2008). One picture immortalised a quietly powerful scene in which one of the Bosnian-Dutch people portrayed, who is trained as a soldier, talks to one of the Dutch soldiers with whom he shares the same professional training, but who had previously, in fact in the same week, continued to deny the genocide on a television programme, which also made the interaction difficult for the artists, who were first-hand witnesses to the war.

The project received extensive media coverage. The artists were present in almost all Dutch newspapers throughout the year, until the city of The Hague decided to adopt a plan encompassing what the artists actually wanted; a permanent national monument to commemorate the genocide of Bosnian Muslims in 1995. Srebrenica is a Dutch History was then a test of what it should represent, what it should look like and many other questions that the project was able to open up as a concrete and both Dutch and Bosnian issue. In this sense, the art project could be seen as a completed art prototype that maintains its own status as an art project, while at the same time constituting an ongoing laboratory for the final goal to be achieved, as an epistemic and scientific process.

The ethereality and elegance of portraits as like as of that by Šejla Kamerić, stand in stark contrast to the stories told, underlining the subversive, iconic action of artistic communication, where beauty, in the widest sense, still represents the disillusioned hope for the future, resumed in black and white, in the coexistence of the bad and the good, the murkiness and the purity of human life, with which the Bosnian Girls collective has established an aesthetic and political continuity over time. This is why it was so important to choose a fashion photographer like Rubin de Puy, for whom "images are opportunities for real human connection and, by sharing them with the world, allow us to participate in such moments."