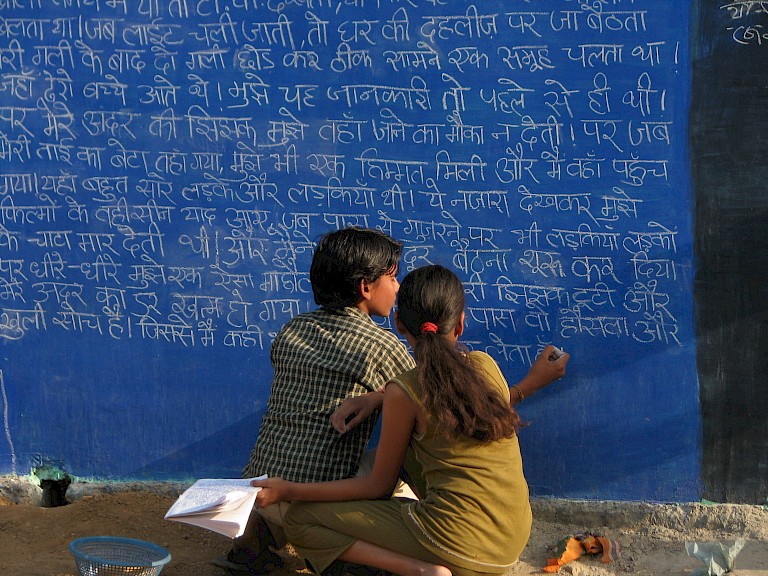

Like many projects in the community arts tradition, The Park relied on the skillful navigation of local antagonisms, and the brokering of alliances in the area, to achieve its objective. Roy spent several months conducting workshops in J-Block and its immediate vicinity, building relationships with locals, and organizing with collaborators, before launching a banner campaign against public littering. This was accompanied by collective action involving neighborhood children and youth in the cleaning up of the park. She also painted a large wall blue, furnishing the community with a canvas to share their thoughts. A 13-year-old participant said, “The wall was an invitation to everyone to speak their minds. We wrote about the park, drew scenes of women resting under the banyan tree, children playing on swings and sliders.”

Roy effectively facilitated a collective redesign of the park based on conversations with the community and engagement with the municipal authorities (for example, obtaining permissions for various interventions). The collaborative nature of the project meant that the artist had to compromise significantly. For instance, where she wanted more greenery, locals wanted barbed wire. Where she would have preferred an open space, women instead wanted a segregated space to “feel safe, away from the men.” In Roy’s opinion, these compromises were necessary “to create an artwork that truly belongs to the people.”

The Park was commendable as a public work that blurred the boundaries between art and activism. Taking approximately two years from start to end, it exemplified an organic, grassroots process of social and spatial transformation. One point of excellence was the way in which the project collectively altered patterns of usage in the park. Another was the sensitivity the artist displayed in subjugating her own desires for the park to a collective set of local expectations and needs; Roy understood the difference between personal and collective creation/expression. The Park provides us with evidence that art can play a crucial role in reshaping public spaces and their associated social habits, and that artists, rather than government authorities or private interests, often prove to be the thought leaders and catalysts for solving pressing social problems. Projects like this suggest that artists should be given more importance in considerations relating to urban revitalization and community development.

All copyright belongs to Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts, Shanghai University.