Milton Keynes, the largest settlement in Buckinghamshire, England, about 50 miles (80 km) north-west of London, is one of Britain's most prominent examples of the 1960s "New Towns Movement", one of the major urban programmes in post-war Britain, established by the New Towns Act of 1946 as the boldest solution to the post-war housing problem. As the social and cultural historian Mark Clapson explains, 'It was a keystone in the reconstruction of the so-called 'New Jerusalem' promised by the Labour Party in its election campaign towards the end of the war. Parts of the population of bombed-out and overcrowded cities were dispersed to planned new communities in the provinces." (Clapson, 2017)

Milton Keynes is also the largest 'new town' in the UK. In a way, Liesegang says, it's a successful town because people like living there, except for the lack of a town centre. So the artists have tried to investigate how the town centre might develop in the future and what it might look like. The exploration was an attempt to learn how we might build on this very modernist, and low-density town and bring the notion of city centre to life.

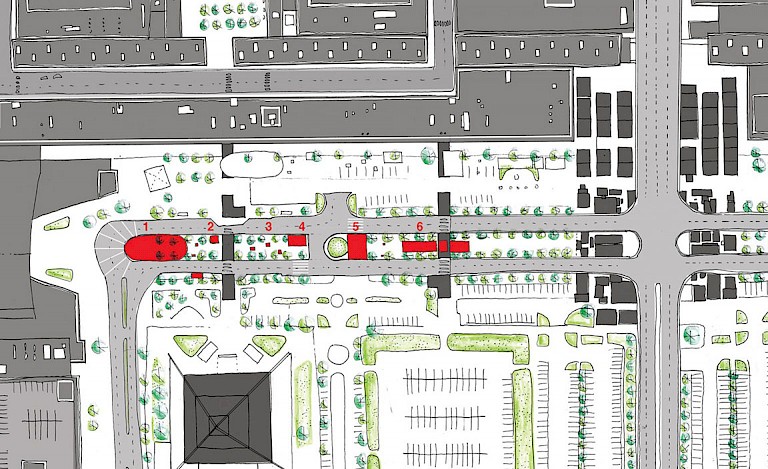

As in many preplanned cities such as Milton Keynes, there is a huge shopping centre (part of the original design). The art intervention was erected here. In essence, this place was chosen because it appears to be an actual city centre. It is basically the spot where buses normally come in, and turn around, dropping off the people at the shopping centre. Liesegang views the riders as arriving, and then "disappearing" into the shopping centre. In this, public life on the street is not visible, even though there are cultural institutions like a museum, a theatre, and a cinema.

In this sense, the landscaping doesn't have any kind of destination, density, or landmarks. Even the local McDonald's doesn't really face the street. In essence, the destination is the shopping centre. The festival set out to explore different ways of living in this space, to explore new ways of seeing and using the area as a potential city centre. An open call was made to local artists and architects to build a "Utopia Station."

A key characteristic of Milton Keynes is flatness. The artists took this geological feature as an opportunity, building a panoramic point at the top of the Utopia Station platform. This vantage point offered a view over the entire city, allowing visitors see the city from a "plan" perspective. Visitors were "... getting inspired by different scales and views of the city," as Jan explains, "... it was a kind of polystyrene model that you could like to take the ideas from one floor to the other. Then people would come back to the lower part of the structure, where a model of the whole city was continuously built and rebuilt according to the new ideas coming from people."

In fact, Utopia Station was built on several levels so that visitors and participants could have multiple experiences of the place, looking at it from different perspectives. Participants could see a model of the city on the ground floor, then go upstairs, experience a workshop of sorts, and then go upstairs and see the real city they were working on. The building itself was designed as a kind of container and an instrument to collect different ideas about the future of Milton Keynes.

Utopia Station offered different participatory spaces and tools. For instance, there was a kind of glass house; a studio where people were invited to answer a questionnaire about their ideas of the city and how they thought or dreamed it should be. Here, the participants were able to begin drawing their ideas. Upstairs there was a model-making studio where some young architects built models based directly on answers to questionnaires, from the different visions that people had. Utopia Station became a complex urban model, built to help people garner an understanding of how planning works.

The view from the platform offered a perspective of the whole city; something like the scale model, made and installed in the lower level of Utopia nStation by the urban planners Téléinternetcafé (who were the operational side of the project designed by raumlabor). The model evolved from the results of the questionnaire filled by the participants. It became more like the participants ideas and dreams for Milton Keynes in the future.

The model did not represent a single idea of Milton Keynes, but rather created a pluralistic imaginary city, composed of different examples, in different places of how the city might develop; something like a contemporary image of the Tower of Babel. As Liesegang notes, the artists and architects themselves had an unclear idea, "mixed feelings" about Milton Keynes.

Utopia Station could also be conceived as a container of imaginaries, models, and a structure that served to test new methods of co-planning: Participants could see a model of the city on the ground floor, follow on by taking part in a workshop on the upper floor, then go upstairs to see the real city they were working on, where there was also the model-making studio where models of an alternate, reimagined Milton Keynes might be realised. Here is an example of the architects realising (in a model) something raised by the participants: Liesegang explained a participant observed the city needed space for children to play and have fun. Based on this, the architects designed and modelled varying kinds of playgrounds.

The festival lasted for two weeks. However, the structures were built beforehand. An illustrated video on the raumlabor website depicts the shared public workshop process, all design steps, and the operational mechanisms that led to the creation of the model and structure.

The model of the "pluri-city" was built, and rebuilt through a process of continuous making and remaking of place, stimulating and manifesting continuous social participation and change in the relationship with the city and its parts. Liesegang says "... it was not just a one-off scenario. It was like rebuilding within the whole." Almost every day there was a new, growing city, combined with references to utopian cities conceived in modern times, whose images and plans were hung on the wall of the workshop space. In this way, raumlabor inspired real collective research that worked like a creative machine for possible urban futures.

The greatest impact of the project is in people's minds, because raumlabor created a meeting place, a centre, that didn't exist, and because of the high level of experience that Utopia Station gave to the residents, who were involved in the potential planning of their city, their future living space. The medium, and long-term impact of the inspiration and services offered is difficult to measure, but for the first time, people experienced how to change the city, and how to become planners for a day.

Participants discovered the wide boulevard, usually full of cars, could be rethought and redesigned as a playground for children, for example, as it was closed for the entire duration of the festival and they could reappropriate the entire space without danger. In this way, Utopia Station can be seen as a real urban education project.

As the festival was funded by the City of Milton Keynes, the everyone from the planning department and the Mayor were there to see and discuss the results of the project, the results of these tests, with the artists and the other participants, taking away some criticism and some ideas. In fact, when the festival ended, the debate between the local authorities and the architects about how to redesign this aspect of the city continued. The aim of the exploration was not the closure of the street to traffic, but to test the outcome through creative co-building processes. This implementation of the city models was useful to facilitate people's interpretation of urban planning and visualisation of their own ideas of the future city.

The project also recalls the human need for physical relationships with space and between people, which the project of creating an ideal place can establish. At the same time, it created a kind of physical social network that was ironically called "Beds United", a programme that allowed the artists, architects and urban planners to stay in the homes of local people in order to cross their stories. Participation was promoted through the creation of comic videos that were played by them and by the people and broadcast on local television. So, finally, the project re-created a physical relationship with the space. The researcher feels this has a lot of value: It makes the participation real and at the same time, moves Milton Keynes towards a more ideal place.

From a geo-aesthetic point of view, the project provided the city with a missing landmark, a point of visual and cognitive reference through which we assign a mythical value to space - which by its very nature transcends space and time, as shown by the places that we know do not exist but that humans, as the geographer Yi-Fu Tuan has said, will continue to seek. It is a site through which we also establish an emotional-sensory daily relationship.

During the design process, raumlabor decided to create a kind of star on top of the building, a kind of "signifier of the centre", clearly reminiscent of The City Crown, written by the German architect Bruno Taut under the influence of the First World War; a critical text for the history of European modernism, encouraging young architects to imagine and build the ideal instead of perpetuating the everyday (Altenmüller, Mindrup, 2009).

Taut wrote it to replace missing ancient landmarks such as the castles and bell towers, images that are stratified in the cultural memory of citizens and play a role in imagining their future in the city when it needed to be reimagined and rebuilt. Taut promoted a utopian urban concept in which people would live in a garden city of 'apolitical socialism' and peaceful cooperation around a single, purposeless, crystalline structure. This structure was based on the development of the garden city concept by the English urban planner and founder of the garden city movement, Ebenezer Howard, and the rural aesthetics of the Austrian architect, painter and urban theorist, Camillo Sitte. Taut merged the two notions with his own concept of the 'city crown.' This concept was a central underpinning of Utopia Station; Taut imagined a utopian garden city of 300,000 inhabitants in The City Crown, and included in his book over 40 other historical and contemporary examples of utopian cities, developed around a central communal structure of glass.

With an objective approach, raumlabor has identified and made visible the essence of Milton Keynes by referring to early modernism: The modernist city, and therefore modernist thinking, has no centre, but only districts, although it gives the modernist city a different, more transcendental hue. In Utopia Station, this concept was taken as a starting point to somehow break the pragmatics of the "scaffolding structure," as Liesegang puts it, because they "wanted to add something that was just beyond reason, that didn't really make sense, like creating a place that people could see from different sides, for example using both red and blue sides and all the sticks on top, so that when you walk around it, the colours keep changing", in order to challenge certainties by creating a "tectonic gesture." Finally, Utopia Station was a challenge to the modernist institution of the gigantic shopping centre. It is also a container of artificial worlds and spaces often designed as historical "fakes", because they recall the memories of people who go through an unconscious process of aesthetisation of the world and societies, as Yves Michaud would say (although, according to Liesegang, unlike people, architects can find modernist purity beautiful and interesting).