The Artist

Aroha Novak (Tūhoe, Ngati Kahungunu and Ngaiterangi) grew up in Ōtepoti / Dunedin, graduated from the Dunedin School of Art in 2007 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master of Fine Arts with Distinction in 2013.

Living and working in Dunedin, Aotearoa–New Zealand, Novak’s work has focused on escapism, utopias and idealism within a capitalist, postcolonial and institutionalised society, frequently working outside of traditional gallery spaces and collaborating with other artists. Her work is often research and project based, drawing out indigenous and local histories that have been forgotten or suppressed, exploring social, political and economic inequality still prevalent in contemporary society. She has a deep interest in Māori language (Te Reo) and researching/highlighting forgotten histories/information about whenua (the land).

Novak is a multidisciplinary artist, letting the concept dictate the materials used by employing a new approach to each project. She has exhibited in both solo and group exhibitions since 2008.

Artists were approached by the wider project’s curator. Selection for the project was based more on existing relationships - Ōtepoti Dunedin has a close, dynamic and diverse art/music practitioner scene. Each artist had a substantial art practice(s) - sound works, performance, ceramics, sculpture, drawing and research practices.

Projects were an opportunity for artists to research, create new work, explore these ideas in the realm of the public space, moving through and relating to the changing environments. The curator comments:

The brief was open - any restrictions were around the physicality of the cargo bike - what could fit? What terrain we could go on? What was possible? How could audiences interact? Instead of a written proposal from artists, we would meet at sites, drink tea and coffee, meet at our local pub or restaurant, and discuss ideas - an open dialogue - a back and forth of discussion, possibilities and problem solving each project would bring. I believe artists enjoyed the opportunity to work and explore in these experimental, and not always predictable ways, as much as I did facilitating and supporting these projects.

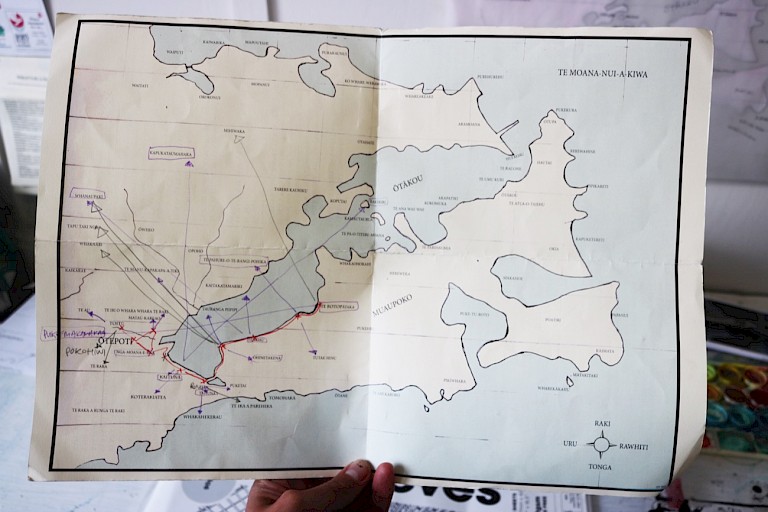

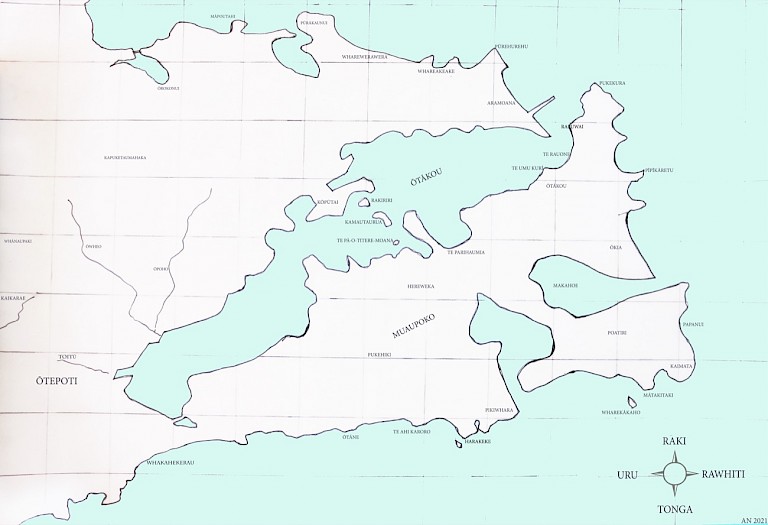

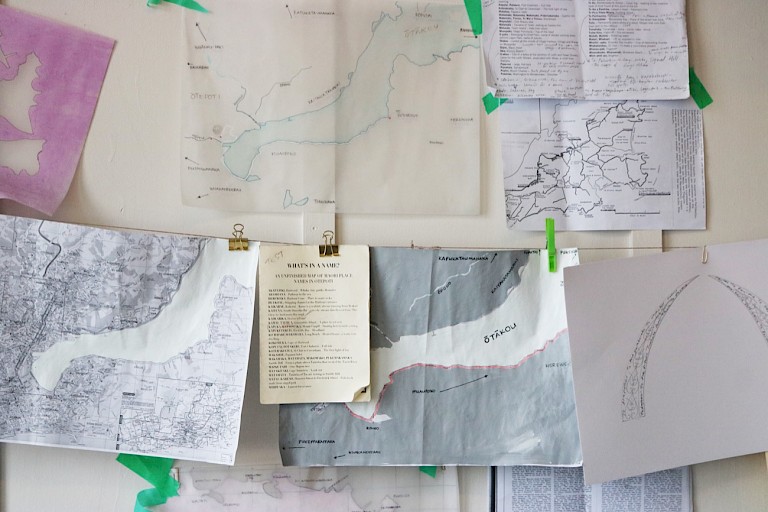

The planning and research for this project uncovered and adhered to many cultural procedures. Novak explained the two strands of research: (1) Tuatahi: researching Māori place names from a number of resources in the Public Library, reference section and the Hocken Library, talking to people and investigating the Ka Haru Manu Kai Tahu mapping website. (2) Tuarua; Finding maps and studying the topography of Ōtepoti as references and drawing these.

Anti-spectacular but strongly poetic, What's in a name? An Unfinished Map of Māori Place Names in Ōtepoti is a quiet and personal gesture reflective of a broader desire to reconnect with place and history in an increasingly dematerialised and disembodied virtual existence. In this sense it is a timely and very powerful art work.

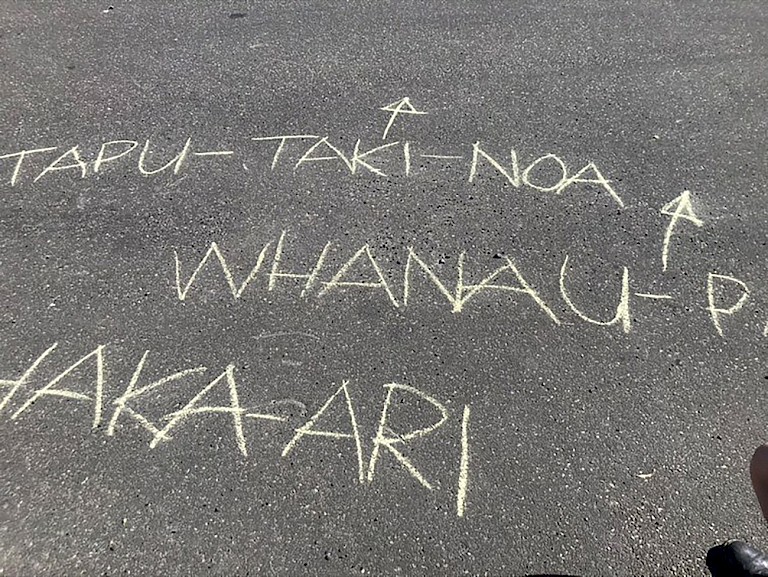

The tools are simple – people, story, and bicycles – but the broader action and resonance of the art work go far beyond to create significant impact. Novak’s art work reconstructs and rebuilds understanding of place. When Europeans arrived in Aotearoa–New Zealand they surveyed, acquired, and dramatically altered the landscape, replacing traditional names. Settlers named towns or rivers after British historical events, famous politicians or aristocrats (who had never set foot in this place), or the areas they had come from. European naming displaced Māori names, pressing upon the land a foreign set of values imported from other cultures and countries. Māori place naming, however tends to record significant events and ancestors from an area. This tradition also uses natural features (such as water sources and mountains) to describe, identify, or caution against uses of the space, assisting with a map-less way finding in an oral culture. Places are granted meaning through their links to people and activity. Many Māori still feel mamae (hurt or grief) about lost place names. As the bicycles took part in the route around the Otago peninsula they flew Tino Rangatiratanga flags (the national Māori flag, used to represent the indigenous people of New Zealand), which situated this project within a dialogue about first peoples.

Rather than focusing on decolonising the places visited, Novak’s art work instead takes a re-indigenising approach, one that adds or reinstates elements of Māori culture and becomes part of a movement to go beyond tokenistic gestures of recognition or inclusion to meaningfully change practices and structures.

This art work is a participatory and performative piece in the vein of early Fluxus artists in which actions aligned with a spirit of rebellion create subtle gestures but enormous ripples across social and political histories. Contemporary art practice is united by a singular objective: to engage the viewer. To capture attention and open space for a thought-provoking experience is key, especially so in participatory projects. Characterised by their interactive nature, socially engaged or participatory art draws on people as a material in the realisation of the art work.

In this art work Aroha Novak has created a totally immersive experience for her participants, granting them the permission to engage on a tangible level, in bringing the art work into existence. Participating in What’s in a Name… offered people the opportunity to explore the intricate relationship between history, environment, geography, and identity. It is also important to note that the art work had two distinct phases: the participatory bicycle aspect, and afterwards the display of the map showing customary Māori place names that formed part of an exhibition in a central city shop front window temporary exhibition space.