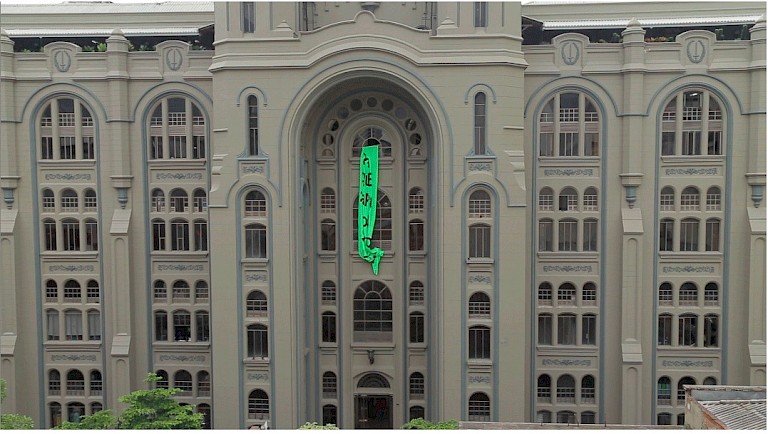

The project consisted of a 4 meters wide X 12 meters tall banner, almost like a vertical flag, that was surreptitiously thrown out a window from the National Palace (former government center now a shopping mall) with a phrase that stated, “Why shoes if there is no house”, a famous quote from the Rose Seller a 1990’s movie made in Medellin.

The creating background goes back to two main things. On one hand, Henry’s interest in crossing symbolic meanings in this case the connotation of the building itself with a power, justice and architectural structure and the social inequalities that are so evident in Medellin, particularly in the city center where the National Palace is located.

During the time Henry was at Taller 7, the artist in residency space that hosted him in Medellin, (since it was in the center of the city), he implemented a daily routine to walk around downtown, pushing himself a little further every time to get to know the dynamics of it.

Between 1980’s and 2000’s downtown Medellín underwent a significant physical transformation, the government buildings changed their use, and the public officials were moved to new buildings a little further from the center. There were several iconic changes, including the mayor’s office that changed into a museum, and the government center into a shopping mall. Both buildings are part of Medellin’s Art Deco Architecture from the 1920’s and both buildings took vastly different paths in their use. As expected, new meanings came along.

The flag was made by the artist, using his sewing skills learned from his mother when he was young.

From the researcher -

One of the most important and powerful characteristics of this project is its illegal condition, in that sense the quick or “guerrilla” action installs an artistic / critical gesture which is ephemeral and manifests a reality that is mottled and contradictory. This project enquires in the symbolic of culture pop: the fluorescent green banner he uses is associated with the street marketing of the informal economies that circulate continuously the public spaces of the city's downtown. The phrase Pa’ que zapatos sí no hay casa (What is the need of shoes if there is no house?) comes from the movie by Victor Gaviria, La vendedora de rosas

which was awarded internationally but was specially appreciated by the people from Medellin because it portrays the consequences of narcotraffic in a Medellin that was heavily marked by social inequity in the 1990s and especially because it was filmed with natural actors and actresses. In this instance the line “pa que zapatos sí no hay casa” is said by a drug addict boy that was hired as an extra for the movie but that in reality was a homeless boy. And finally, the Palacio de los Tenis which is a place of temporary confluence of those popular identities, logics and powers.

Adding a layer of sense to the action it was conducted during a Colombia soccer match for the World Cup qualifier. An event that is especially important for many sectors of society, especially for the working class. During the match, that implies that the security will be distracted and scarce in comparison to the amount of vigilance to which the Palacio de los Tenis is usually subjected to, the artist and his collaborators put up the banner in a window. The action is not done illegally in statal terms but surreptitiously to the non official power dynamics that operate in the city's downtown, and that through violence have erected the legitimacy over fear. because of this even after the work was executed in the public space it keeps being fulfilled through its narrative, in other words in the process for its development beyond its material result. It is this contextual condition the one that makes the whole operation more complex putting it in a place that goes further than just being an anecdotal action and transforms it into an aesthetic operation that keeps on operating. Because of all of this, the project implies a great challenge in its circulation in museo graphical terms since it is not enough with exhibiting its documentation.